|

|

|

With little fanfare, Heathers was released in the spring of 1989. The film vanished from theaters quickly and soon hit the home video market, where it has become a cult classic. But why has this darkly humored flick endured? Why is it more popular now than ever? The answer is simple: it's a great movie, period.

Heathers manages to do what few other teen pics in American film history have done-find the heart of middle-class. Its blade is forged out of biting satire that relentlessly goes after every high school social division that The Breakfast Club tried to canonize.

The Heathers (Shannen Doherty, Lisanne Falk, and Kim Walker) rule Westerburg High with icy stares and cruel pranks. They resemble the cold statues of Greek goddesses that flank them as they engage in their favorite after-school activity: power croquet. The preppies fear them. The jocks lust after them. The geeks worship them. The druggies stay out of their way. And the mousy brains envy them.

Veronica Sawyer (Winona Ryder in her definitive role) was one of those mousy brains who would have been content just hanging out with childhood chum Betty Finn (Renee Estevez) if she hadn't been hand-picked by the Heathers as a peer. Now she "uses her grand IQ to figure out which kind of lip gloss to wear and how to hit three keggers before curfew." In her heart, Veronica is an individual looking for a better way.

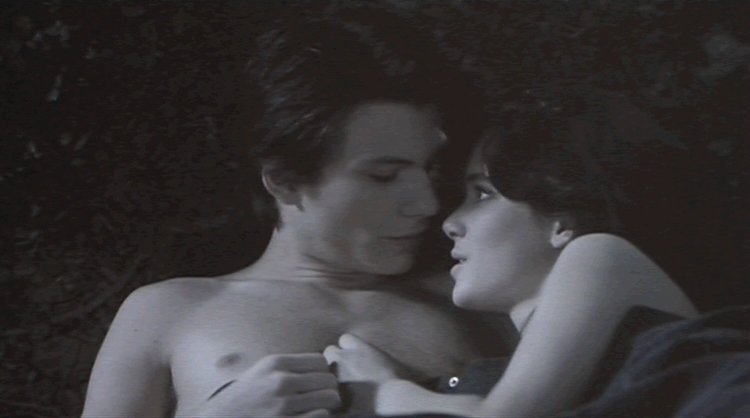

So when J.D. (Christian Slater), the new kid with the Nicholson-esque purr rides into her life, she sees a kindred spirit. Unfortunately she realizes too late that this easy rider with the conspiratorial past and the twisted family life is a raving lunatic.

J.D. entangles Veronica in a web of deceit and staged suicides that shake up the whole school.

Veronica sees that Westerburg is being controlled by a much more dangerous form of conformity than the Heathers ever inflicted, and she needs to make things better, her way. Up to this point in the film, Daniel Waters' excellent, razor sharp script has maintained an edge through macabre humor and knowing jabs at common perceptions, like the overreaction of the school board to the tragedies. However, because of outside forces, the ending seems optimistically out of place.

Rumor has it that in the original treatment, J.D. and Veronica complete the cycle of doom by demolishing Westerburg with a load of dynamite, but the studio (the now-defunct New World Pictures) blanched at the idea of both central characters dying at the end.

However, it's obvious that Waters and director Michael Lehmann (Airheads) did the best they could to remedy the problem as the triumphant but battered Veronica hooks up with the school's other true individual, the lumbering outcast Martha Dumptruck/Dunnstock (Carrie Lynn). In a film where the overall theme is that "conformity kills," it makes perfect sense that the individual spirit should ultimately claim victory.

On a technical level, Heathers is much sharper than the average teen comedy. Director Lehmann expands on the outrageousness of the script, and by working with cinematographer Francis Kenny (Pump Up the Volume) and composer David Newman (Bill and Ted's Excellent Adventure), Lehmann creates a world that is at once both absurd and sublime.

And it is rare that an American film treats costume colorings as importantly as in Heathers. The script hints at a color scheme for all the major characters and costume designer Rudy Dillon takes the notion to a subtle yet all-encompassing level.

The "uniforms" the Heathers wear match the colors of a stop light: red, yellow, and green. Veronica is usually draped in blue, the cool opposite to Heather Chandler's (Kim Walker) power red. But Veronica slips into grays and blacks after she hooks up with J.D. Like the Reaper himself, J.D. is always cloaked in black and after his "suicides" rock Westerburg, the entire student body is infected as black arm bands become a fashion staple.

------------------------------------------------------------------------

"Heathers" is not pretty in pink, all pompoms and puppy love, but a cracked satire of the teen genre.

Caught somewhere between the numbing amorality of "River's Edge" and the heartfelt sap of John Hughes, "Heathers" chides the pursuit of popularity as it tackles the thornier topic of teen-age suicide.

These teens aren't boy-crazy, giggly or mall-fixated. They are political animals, and in the heroine's case especially, their characters are fresh and full-bodied. Winona Ryder is the focus as Veronica, the fourth most popular girl at Westerberg High in Sherwood, Ohio. Though only a junior, she has made it to the top. Shaking off her grade-school-geek pals, she has become a member of the Heathers -- an exclusive clique named for its founders -- Heather Chandler (Kim Walker), Heather Duke (Shannen Doherty) and Heather McNamara (Lisanne Falk).

"Heathers" is the rare teen movie that looks at high school feudalism from an insider's lofty perspective. There's no easy-to-love underdog looking to get in, but rather this stunning quartet for whom dweebs are doormats. To maintain their power, the Heathers wipe their feet on the fat and the unfashionable.

When Veronica questions their cruelty, Heather Chandler explains that popularity is not for weaklings. "Real life sucks a loser dry," says the little despot, who rules with an iron fist and a velvet hair ribbon. With perfect accessories and a menacing smile, she might be the evil queen of "Snow White" in a wardrobe from Benetton.

Though Veronica thinks of Heather the First as her best friend, she wishes she were dead. Scribbling furiously in her diary, she confesses her growing ambivalence about her place at Heather's side. Caught in that pimple-pitted purgatory between childhood and maturity, she tentatively starts to carve out an independent personality. Rebelliously she takes up with a transfer student, a socially unacceptable, filthy rich juvenile delinquent.

J.D. (Christian Slater), James Dean by way of Faust, mesmerizes Veronica -- one burning look in the cafeteria leads to a game of strip croquet, which leads to manslaughter. Imagining him a kindred spirit, she tells him her fantasies about Heather. A man of action, he takes it further, becoming a guerrilla in a personal war against the popular.

Kim Walker creates such a delicious vixen in Heather, it's a shame she has to go so soon, but go she must. J.D. "accidentally" kills her when he dares her to drink a kitchen cleaner cocktail. Veronica, a gifted forger, writes a suicide note: "People think just because you're beautiful and popular, life is easy and fun. No one understood that I had feelings too." To Veronica's everlasting astonishment, Heather becomes a media martyr, memorialized in glowing sound bites.

Asked what she will be doing after the funeral, Veronica says, "I dunno. Mourn, maybe watch some TV." For a while she is glad to be rid of Heather, figuring the world will be a better place without her. Alas, Heather the Second, perhaps even nastier, is crowned; the body count climbs and suicide becomes the "in" thing at Westerberg High.

Deadpan reactions to grievous ills are the stuff of black comedy, but the notion that murder-suicide is funny is bound to cause a ruckus. But Daniel Waters, who based the screenplay on a high school newspaper column, means to send up suicide, to strip it of any glamor or nobility. He and debuting director Michael Lehmann haven't quite done that, though they have devised a strangely hilarious morality play.

The buoyancy of tone and raw young colors contrast with the heroine's deepening guilt and growing wisdom. "You're not a rebel. You're a psycho," she says. "You say tomato and I say tomahto," he says. And love is snuffed like a spat-on match.

J.D. is one nasty hombre. Ryder, on the other hand, makes us love her teen-age murderess, a bright, funny girl with a little Bonnie Parker in her. She is the most likable, best-drawn young adult protagonist since the sexual innocent of "Gregory's Girl."

"Heathers" is about the loss of a deeper innocence, an internal passage made without the aid of oblivious parents, idiotic faculty or babbling ministers. For all the talk of suicide, the moral of the story is one of America's best loved: All people are created equal -- even the nerds.